By David Stahler Jr.

I know what you’re probably thinking, but no—this isn’t a tribute to that fuzzy little red muppet begging to be tickled. This is instead a paean to a piece of equipment that I started using in the classroom a few years ago, one that totally transformed how I teach literature and writing at Lyndon Institute. Basically, a digital version of the classic overhead projector, the device is technically known as a “document camera,” but—like Kleenex or Xerox or Ski-Doo—everyone calls it by the brand name of the company that makes the most popular model: ELMO.

The company was originally founded in Japan as Sakaki Shokai in 1929. After introducing the first 16mm projector in 1927, the company changed its name in 1933 to G.K. Elmo-sha, with ELMO being an acronym for “Electric Light Machine Organization.” Elmo-sha later developed an 8mm projector and a series of hand-held movie cameras before releasing their first overhead projector in 1969. The company went on to establish ELMO USA in the ‘70s, and in 1988 introduced the first document camera, which it has continued to modify and improve over the last several decades along with other educational equipment.

That the ELMO became such an integral part of my classroom may seem strange at first. On the one hand, I’m no technophobe—computers have fascinated me ever since the first desktops came out when I was a boy in the ‘80s; my life is filled with gadgets; and I recognize that technology plays an important role in education, particularly in the STEM and CTE fields.

But…as an English teacher, I’ve resisted a reliance on technology in my own classroom. We spend our days immersed in our devices, our screens, our notifications, so I’ve always tried to make my classroom at least a temporary haven from this modern world of distraction and create a space in which the written word, the text, is sacred. There is beauty in simplicity, and the English classroom is a place where the analog world of paper and pen and healthy dialogue can flourish and offer respite from the digital deluge.

What makes the ELMO special, though, is that—when paired with a projector and a good whiteboard—this digital device actually privileges the analog, elevating the physical world of paper and pen in a way that makes these ancient tools even more useful and versatile.

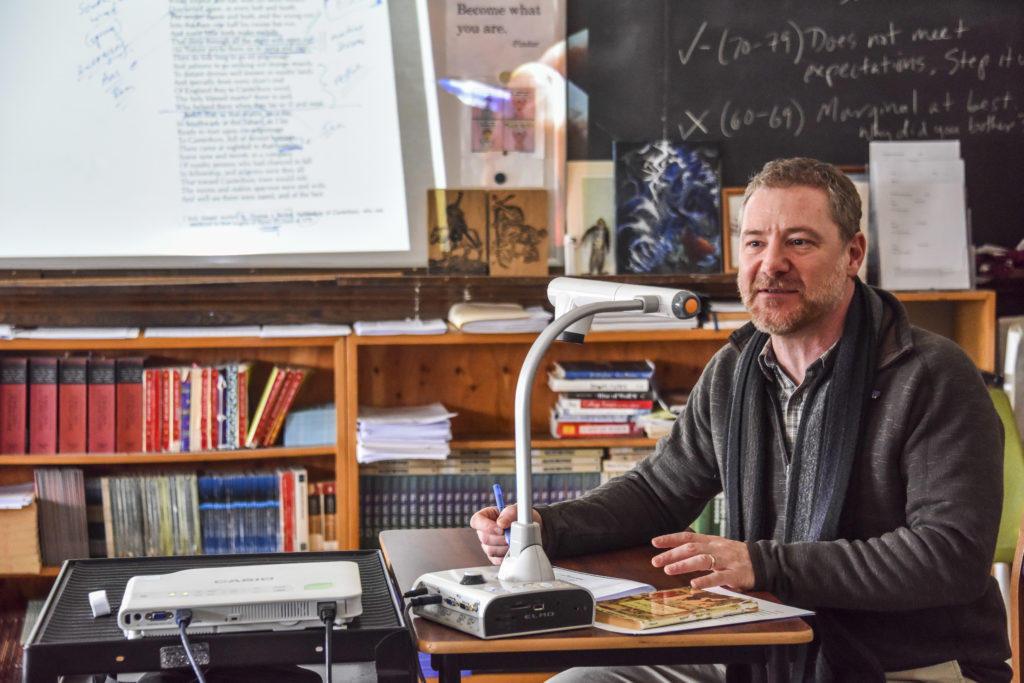

In terms of teaching literature, the ELMO has been a game changer. I start with a physical text—a photocopy of a poem, an essay, a short-story, or a play—and place it under the camera, where it is then projected onto the whiteboard before the class. My students each have been given their own copy. With the words big and bold before us, we read together, stopping frequently to discuss, question, engage. Pen in hand, I mark up the document as we go—bracketing paragraphs, underlining sentences, circling phrases, starring words, making notes in the margins. The students copy my markings and notes onto their copies and add their own.

In the past, I would typically be standing up in front of the class, away from the kids, writing on the board, jotting down fragments of discussion. Now, I’m sitting with the students as we make our way through the literature. It’s a process that turns textual analysis into a communal act—we are all in it together, working as one.

This method offers several advantages. For one, it allows me to model the art of marginalia, a vital academic skill. In the old days, I would tell them to take notes. With the ELMO, I can show them how to do it well. The practice of marking up a text not only helps reinforce ideas as we discuss them but preserves understanding for later use on compositions and tests.

It also does an amazing job sharpening my students’ focus. People are drawn to a giant glowing screen, which the white board effectively becomes; light captures our attention. Side chatter is virtually nonexistent, and all eyes are on the work at hand, though students will sometimes interrupt me as we work: “Can you move the paper?” they’ll ask when I accidentally shift the part of the document, we’re annotating off camera, inadvertently offering me a welcome reminder that they’re engaged.

Marking a text this way or jotting down discussion or lecture notes on blank paper instead of writing them on the board offers another practical advantage—permanence. At the end of every class, I have a written record of our conversation, one I can then photocopy for absent students upon their return or use as a reference in another section of the course or even when preparing for next year’s class.

In terms of teaching writing, the ELMO is just as useful. In the past, I would often ask students to write a paragraph from their composition up on the board, which we would then collectively edit. It’s a helpful way to teach both technical skills and the finer points of style. But the process was tedious—precious minutes of class time would be wasted waiting for students to write their work on the board. With the ELMO, I can take a student paper directly from the pile of freshly submitted essays and project it instantly onto the board. From there, we can get to work editing, either marking the paper itself or editing the projected text directly on the board with a dry erase marker. Even better, short in-class writing activities, such as many of the poetry and flash fiction exercises, I do in Creative Writing and in my weekly Writer’s Workshop club, can be immediately shared up on the board, hot off the press when my students’ interest in what their peers have written is at its sharpest.

At first blush, the ELMO may not seem that different from a traditional overhead projector, but the digital version is far superior to its analog ancestor. The latter, big and clunky, requires the use of transparency sheets—expensive, difficult to make copies with, annoying and messy to write on. It’s tedious and requires advance planning.

The ELMO, in contrast, offers something priceless in the classroom—spontaneity. While discussing the opening lines to Milton’s Paradise Lost and noting his invocation to (a Christian) muse, I can grab a copy of The Odyssey off the shelf and project the introductory lines with Homer’s own invocation to the original muse front and center for an instant comparative analysis. While reading “Musee Des Beaux Arts,” I can pop open an art book and show Breughel’s painting Icarus, the subject of Auden’s great poem, for context. Any book on the shelf or paper from the file cabinet archives can almost instantly be made accessible to the class without having to run to the photocopier or make twenty copies of something that may only be needed briefly. Last year, as we worked our way through Ted Hughes’s poem “Pike” in class, someone asked what a pike actually looked like. A student pulled out his phone and brought up a photo of a great northern pike; We set the phone down under the ELMO, zoomed in the camera, and the fish in all its glory and terror filled the white board. Spontaneity!

For most classroom settings, technology is at its best when it acts in a supporting role and doesn’t dominate the students’ focus or upstage the content. With its simplicity and versatility, its offer of both spontaneity and permanence, the ELMO allows me to make my English classes more focused and better able to target advanced skills. It provides a perfect visual format to compliment the auditory experience of reading aloud and engaging in discussion and dialogue, a digital tool that enhances the analog world of the written and spoken word.

To learn more about our wide ecosystem of connected educational solutions, click here.